Ω Mantra, Nicolas Roses, Pics by Nelly de Boer

by

tf

|

Orientalism up your ass

Text by Riven Ratanavanh

Photo by Mengwen Cao

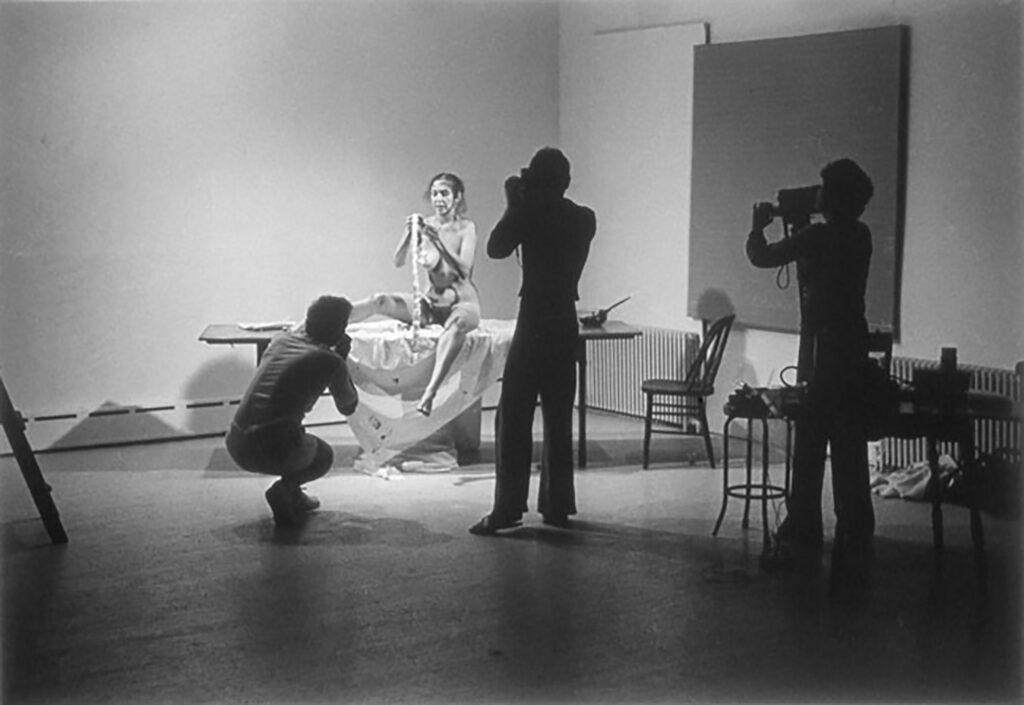

Artist Riven Ratanavanh parses the frisson of sex, race, and power behind his reimagining of Carolee Schneemann’s ‘Interior Scroll’

In 2022, an account called “Asian Guys?” messages me to ask: how are you?

Without havin seen his Grindr profile I wonder if he’s white, but then I think to myself

that doesn’t seem right—his username is too self-proclaimed. Chasers, I reason, aren’t usually all that proud. Not the Asian chasers I’ve encountered.

I look at his profile. He’s Asian. We get chatting. He says he’s looking for something specific.

Looking to train Asian guys to dominate white boys.

I’m not sure yet if my dick is hard but my interest is piqued.

As an East-Southeast Asian transsexual man—or let me say, transmasculine faggot—I grew up as a girl in Thailand, and I was never taught to be assertive, nor to own or be loud and public about my anger. I thought, if Schneemann, a white cis woman, had a lot to say to a white cis man in the ’70s, then I have a lot to say to what cisness and whiteness are doing in the culture around me now. I wanted to pastiche her method but not reproduce its gender essentialisms. I also wanted to bring race to the fore and tease out how erotic power dynamics are intertwined with colonialism. What was I angry about? I was tired of trying to make art, fuck—exist—without being stereotyped as an innately submissive bottom, sexually, psychically, culturally. Scheemann said ‘fuck the man’ by pulling something out of her vagina, amping up whatever ‘feminine indulgence’ had been used to dismiss her work. I said Fuck the white cis man by putting it up his ass, flipping stereotypical roles.

—

Months into my exchange with Asian Guys?, I discover that he not only has a harem of white boys he lends out to the guys he trains, but also a “brainwasher” who makes homework for the boys—hours-long hypnosis videos. The brainwasher can’t find enough porn of Asian men dominating white men to make these videos with, so he resorts to also using footage of Asian men fucking white women instead.

I can’t believe that’s true, so I check. I realize it had never occurred to me to seek out porn through a racialized filter, and realize people often do. I look up “gay Asian man dominates white man” and its variants on Google. Everything that shows up is the reverse, my words spit out in opposite order, despite my carefully composed search. I had even used the proper search operators to specify that I wanted them one way around and not the other. Among the results: “muscular white man fucks Asian bare in the kitchen”, “Asian bottoms pounded by big white cocks (13 scenes!)”, and “WHITE DADDY DOMINATES ASIAN SUB”. Other videos are less racially explicit in their titling, but less than one out of ten feature an Asian top and white bottom. Even fewer feature an Asian dom and white sub, in stark contrast to the majority of videos that center around white domination.

I understand there is a shortage of images–and sometimes you’ve got to see first in order to be able to do.

—

I’m often fetishized as a trans guy for “being the best of both worlds.” Embedded within this idea is the bioessentialist assumption that I possess both “masculine” and “feminine” physical and emotional traits. With the former comes an implied bottomhood, the latter some sort of ability to hold whatever feelings cis white men have about gender or race (guilt, fear, shame, etc.) unsolicited and at any given moment. In other words, I’m responsible for the invisible emotional labor of producing feelings of comfort, ease, or benevolence for those who, situationally, actually hold more power than me. Like my Google search, this situation finds itself scrambled in opposite order.

This is a fiction projected onto me. I can trace the structures of imperialism, gender essentialism, racial hierarchies, the histories of sexual tourism; I can map out pre-existing cultural imaginations from a white, western cis man’s view.

—

At an artist talk I give in 2021, an older white man in the audience of the Q&A prefaces his compliment about the “sensitivity” present within my art with these exact words: “I love Asian men. They are just naturally more submissive, gentle, well-behaved, and feminine.”

—

There’s an overlap between being Asian and trans, some sort of double-effeminization. If, according to the oversimplified math of stereotyping, Asian = effeminate and transmasculine = not a man, still a girl, does that make me doubly emasculated? If I’m trans and Asian, and trans = exotic and Asian = exotic, does that make me doubly exotic? I’m a guy with a pussy, the ultimate oriental boy.

Considering the mechanics of orientalist tropes and methods of their reversal, I wonder if raceplay is a way to get at it. Can I afford to play? Can I afford to not? To some it’s more of a game than not, and they have the luxury to not have to think about it.

—

I’m at a rave in the center of a dance floor occupied mostly by muscle cis gays. A hand grabs me from behind. Something about this feels reminiscent of girlhood, being groped at the club. I turn to look up at him, his face, and decide to let him grind on me for a moment. After the moment, I turn around to assess him with more discernment. I look down at his crotch, and then back up to see him smirking. I think: Okay, you want that? Well, I want this and more. We make out and I press against him, move to take command. He allows it for a brief moment, then he pulls back and recedes into the crowd, weaving away from me. I sensed he wanted a passive bottom and I’m not surprised. I’m satisfied.

—

Can it be discernible when dominance is a part of play, or when it is racism’s erotic life reproducing itself? How can we distinguish desire from the unknowing performance of racial trauma through sexual means?

Indeed, desire and disdain can be one and the same. In Anne Anlin Cheng’s recent book, Ordinary Disasters: How I Stopped Being a Model Minority, she writes of her experiences being stared at by adult white men at age 14, not knowing that such gazes could have been sexual, that they must have only been filled with scorn or hate. I, too, recall experiences of this as a girl. “Sexual desire does not preclude racial disdain,” writes Cheng from the vantage of an adult. “I recognize those looks could have been, and most likely were, combinations of both.”

Through the eyes of the white man, I can exist at once on both ends of the spectrum of desire and disdain—best of both worlds again.

From the vantage point of an adult, I have also come to recognize these two seemingly opposed emotions co-exist at once within me. A mirror of the white man who gazes upon me with both contempt and desire, I recognize this contradictory mix of emotions within myself, save from a different vantage: I feel scorn for the scorn and stereotypes that come my way, yet I want the privileges of whiteness and the proximity to it. And then, a double bind again—perhaps I even feel scorn for wanting.

The logics of colonialism reproduce themselves through tropes of the submissive, infantilized Asian boy in the hand of white daddy. Scholars like Eng-Beng Lim, who write about the intertwinings of race, sexuality, and empire, trace the histories of these tropes from postcolonial empire through to current-day neoliberal globalization. In Brown Boys and Rice Queens, he writes about the practically unquestioned gay racial fetish for the dominant white top and submissive Asian boy and its different incarnations in time and place spanning Asia to (Asian) America. Saturating all areas of life from the performance stage to everyday life, they enable an entrenched colonial dynamic, allowing within it an easy encoding of the interlocked pairing of contempt and desire, a place for it to hide unquestioned.

So double down on the tropes again: look at me through the stereotype of what we could call the oriental boy: effeminate, submissive, pliant; waiting to be tutored and disciplined by the white daddy. Ready to perform for the white bioessentialist gaze, he’s only ever a bottom.

In refusal, I decide to stage a flipped image, the opposite of the cis white male fantasy: I put the white boy under my control, train him to assume a position, discipline him through punishment if he breaks a rule or fails to perform. I cover his face so he is indistinguishable, so they all look the same. He holds the scroll for me between his teeth as I read out the ridiculous things my fetishizers have said to me, then I put it in his ass.

Carolee said of her own performance that she “didn’t want to pull a scroll out of [her] vagina and read it in public, but the culture’s terror of [her] making overt what it wished to suppress fueled the image.” Our culture’s lack, or even its depletion—of imagery fuelled the image I wished to make overt; of role reversal on a racial level, of the difference between pulling something out and shoving something in. Did it cause terror? The audience at my show was saturated with queer and trans people of color who reported a handful of cis white men in the audience sweating, looking away, or trying not to look.

Yet maybe the image in its overtness oversimplifies the situation behind the scenes. In BDSM, the submissive party is always, in a sense, the one in power: free to say yes or no, to give consent or revoke it. Without these measures, play can become abuse. In making this work, I choose to play, but play involves labor. There’s parts of care in it, in choosing to engage and be in relation with whiteness. In other words, I’m not a mirror image of the white man.

Among my most defining memories growing up in Thailand are the times when white tourists or expats would joke that we all looked the same when they couldn’t pronounce or remember our names. I remember that my Thai-Chinese aunties and uncles would say in jest that all white people look the same. But I also saw them fawn over white people, motivated by a sense of dependency, economic or otherwise. In Thailand, the Asian chaser doesn’t exist. The white man is distinguished, is purchasing power, is cultural capital, is a promise, is a savior. We chase, and the white man is a fetish—but we play in a compromised position, against odds already set.

—

Post show, I share images of the performance on my Instagram, and connect my Instagram to my Grindr profile.

A blank profile writes me: I’m so interested in how a really tall white respectful guy can be incorporated into your kinks… interested in a tall white slave? I’ll do anything kink related for u. But then he becomes terribly persistent, sending message after message in a row without so much as waiting for a response. My initial amusement becomes annoyance becomes concern.

—

I’m back to square one. Even though he’s saying he wants whatever I want, the persistence says he wants me to give him what he wants. Again, I become surface and utility. Call it fetish. It’s a turn off when someone presupposes I’m one thing and not multiple. The performance wasn’t supposed to cement my position as a top or a dom.

If Schneemann was discontent with the expectations of her culture, my discontent is with the restrictive molds of our colonial legacies. I’m not sure if I can reshape colonialism’s erotic life and how it moves through the culture, but at least I can imagine something new for myself, carve out space to be more than.

—

A month after the show, I tell Asian Guys about it. I send him three texts over the course of a month. No response. His profile is also suddenly gone from Grindr. The last time we talked was in May. We had been talking since 2022. There was not a single time he didn’t reply over the span of those two years. And now, nothing.

We never met in the flesh. I have one picture of his face he sent over Grindr that I never screenshotted. If he’s real, he works in financial or management consulting and lives in Queens. I never met the white boy he meant to give to me. I was on the brink of it—wanted to—but couldn’t quite bring myself to. His methods were too rigid for my taste.

For all I know, Asian Guys is a concept. Maybe he never existed. Yet, this show wouldn’t have happened without him, nor my clarified thoughts about race and gender. So in some way, his imaginary lives.

Carolee Schneemann, Interior Scroll, 1975. Women Artists Here and Now, East Hampton, NY. Photographs by Anthony McCall. (c) Carolee Schneemann Foundation

Source https://www.documentjournal.com/2024/12/riven-ratanavanh-sex-race-a/

Open letter to Jerome Bel by Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez

Dear Jerome,

A while ago someone told me a story that went more or less like this:

A group of scientists were tracking the migratory route of a particular bird species. For some time they noticed an anomaly in the pattern: an important part of the flock would stop halfway, on an island, instead of finishing the whole journey. This stop implied a risk for the whole species.

The scientists were unaware of what caused this unusual behavior, until they realized that an oldwoman from the island used to feed the birds, and so they stayed. The group of scientists went to see the woman, explaining to her the situation and after asking her to stop feeding the birds, she agreed.

But during the following migration season, the birds stopped on the island again and the scientists noticed she was still giving them food. When they confronted the old woman, she confessed that her husband had Alzheimer’s, and that the birds’ presence was the only thing that brought him back to the present time, the only time of the year were they could still experience something together.

How do you convince someone that, sometimes, their personal interest cannot be placed above the greater good?

In the beginning was the word

When, more than a year ago, I heard about your campaigning against air travel in the performing arts field, I remembered that story. I felt implicated in the discussion and I found that your impulse to speak up on the issue was praiseworthy.

As time went by

Your ideas kept spinning in my head, and not in a peaceful way at all. There was quite an awkward feeling attached to them. I scribbled some notes in my diary and then forgot about it. During the next few months, every now and then Facebook’s algorithm would show me one of your posts and, with it, the thought of this campaign would come back, until one day a friend of mine asked me for my opinion on the matter, and so I decided to organize my ideas and share them with you.

Lost in translation

And so this text is a reaction to ideas you have shared on social media and in some articles and interviews I was able to find. Most of the time this information came to me in English, but sometimes I read you in Spanish via Google translator from French; so, although I get your main arguments, there could be nuances, details or colors I am missing.

My own private overview

What you propose deserves to be discussed thoroughly, and in order to do that we must consider the complexities it entails. It would seem as though what started as a personal decision—refusing to use air travel for your work—developed into a more general and ambitious call for the performance art field as a whole. Something like “the performance art field needs to drastically change its habits in order to reduce its carbon footprint. We need to stop airplane travel and look for other ways of sharing”.

Trump vs. Thunberg

At first, your proposal seems impeccable. What wretched soul wouldn’t acknowledge that the planet, our home, is at grave risk and that we must act now? What kind of person would oppose saving our planet for their own personal interest? Who wants to be that Donald Trump who stands against Greta Thunberg?

+

Asymmetry

No measure is ever applied in a vacuum. Measures are carried out by specific people within specific contexts. When you ask the performing arts field to proceed in a new way, it is clear that it would affect different people in different ways, and these effects should unfold asymmetrically.

1%

You are one of the strongest voices in today’s international scene and you belong to the most privileged 1% of our art world. You also come from a country that allocates one of the greatest budgets for art production in the world.

Inverted Occupy Wall Street

I read in one of your interviews that you decided to stop travelling but had your assistants move from Lima to Hong Kong. At some point, you felt that this strategy was hypocritical and so you decided not to use air travel for your work at all. I think you made this decision out of consistency and I believe it came from a legitimate concern. Although I share this concern, I can’t help but wonder: how can a vast majority (of people, collectives and associations), with diverse working conditions, endorse this transformative proposal?

Important note

I don’t mean to reduce your proposal and arguments to your nationality or your position in the field. However, I think it is important to situate them and to point out that no proposition can be detached from its place of enunciation.

I would like to ask the same of you when you read this letter: that you keep in mind where is it written from, without limiting it to its origin.

Are we all equally responsible?

One of the issues we face in the climate crisis struggle is that we all are in the same boat, but we travel in different seats.

About his journey to America, Mayakovski once said that those in first-class throw up wherever they want, those in second-class throw up on those in third, and the later throw up on themselves.

+

Unaware

Just as I am familiar with your artistic career, I am unaware of your personal history in regard to activism. I have asked around and nobody knows much (please correct me if I’m wrong). Because of my context and because of the path I have walked, I am familiar with the overwhelming excitement that comes from finding a cause bigger than oneself, and how one ends up looking at the world through this lens alone. It is also important to remember that many other equally legitimate causes coexist with ours.

A view from the bridge

Since you are trying to modify a model that involves so many people, I think it is important to share with you the way I see things from here, from the other side of the bridge.

Our case

Cultural investment in Mexico is greater than the Latin American median, although it will always be minor compared to other countries; and people are rarely able to make a living out of theatre exclusively. I am not interested in presenting myself as a victim; we (Lagartijas tiradas al sol) belong to a privileged sector of the Mexican performing arts field. Throughout the past eighteen years of our group’s existence, we have built a relationship with rich countries that has allowed us to maintain an autonomous artistic project.

Currency 1 = 24.9

People chose to migrate and earn in euros because the exchange rate between the euro and other currencies is advantageous. Similarly, artists and companies are able to finance projects at home given these exchange rates, as many Latin American companies live of performing in countries with a stronger currency.

Form is content

When I read that you are rehearsing a piece in Taiwan with a dancer from your studio, I find it fascinating. But this project took place (I suppose) because someone commissioned it and paid you for it. For many companies it does not work this way. One usually produces their work however they can, brings it to the world and then waits for someone to be interested in programing it. Working on commission happens in a very reduced part of the world. I wonder: out of the more than 193 existing countries, how many have institutions that commission performing arts projects?

Planes and trains

Europe is a small continent with a significant railroad network. It is not necessary to explain this to you, because you know it rather well, but it is not the case in the rest of the world. There is not a single country in Latin America with a strong railroad system, and the distances are so long that even inside a country it can take several days to travel from one city to another, while travelling to another country could take weeks. Your proposal sounds good for and from Europe, but if we apply your standard to everybody else, it would condemn us to only work locally.

The pedagogy of theatre

Performing arts have the added pedagogical difficulty that they can only be experienced live. When a film student hears their professor stating something in class, they can always go and compare those thoughts with an Ackerman, a Kiarostami, or anyone else’s film, for that matter. This isn’t the case for performing arts. Students have to “believe” what professors affirm, in lack of factual verification. When one lives far from the art capitals, it’s harder to stop believing.

Festivals and artists

It is clear that performing arts festivals have a huge impact on artists who grow up being spectators. The proposal to cut flights implies leaving thousands of artists without the possibility of watching different kinds of work. Theatre festivals in Latin America are utterly important as an entry point to other ways of thinking performance.

Won’t someone please think of the audience!

Who benefits from a foreign company’s performance?

If, as we say, performing arts have a value for those who experience them, the discussion cannot leave the audience out, nor the effect these modifications you propose would have on them. I strongly believe that performing arts do have value for those who experience them, that they do make our lives better, that they endow us with will to live.

We need to talk about Kevin

It would seem as if, when we talk about climate crisis, all of the other spheres of life should give in, and that, at least in this case, the ends justify the means. But it shouldn´t be like that, not always like that. Far from the legitimate (and urgent) concern to produce a performing arts field as clean as possible, it wouldn’t hurt to ponder whether we would want to cherish anything else.

+

Frie Leysen

In a Facebook post where you say goodbye to Frie, you thank her for her worthy legacy and for driving a system that, you conclude, is not sustainable anymore and needs to change.

No doubt she pushed for and created various international festivals (implying tons of flights) for the sake of supporting artists from different latitudes and making them part of an international performing arts circuit. Mobility was the consequence of that will to integrate other voices, not its cause. So we should be more careful when we talk about a model and what parts of it should be redesigned.

Do European festivals belong to Europeans?

Yes and no.

It would seem…

Without a larger program, your proposal would mean yet a greater concentration of resources and cultural capital in the richest cities of the world. It would mean that many of the decentralization and diversification efforts undertaken for many years now, would be threatened. It would mean that Europe would become, even more so, an island of harder and harder access, one that can barely listen to what happens away from its shores.

Please don’t get me wrong

I’m not trying to say that the current model must prevail, that we should preserve it without change. Not at all. I’m convinced, as far as you are, that we need to make multiple changes in the way performing arts are produced and shown. But there are many different kinds of changes, and if the one you propose attempts to establish an ethical standard, it should take into account the multiple realities we live in, and the degrees of attainability of the model for those realities.

+

Be realistic: demand the impossible

Causing an impression with a “radical” statement is a valid strategy, but a strong statement shouldn’t make us forget the material nature of the change we are proposing.

Symbols matter

I think it would be a mistake to overlook the symbolic character of the action you propose: if the performing arts world stopped flying, the problem would remain. In other words, in the face of this given problem, yours is a very valuable political statement but it is not an action plan to solve it.

No confusion

I am not saying that because the problem cannot be fixed from within our field we should do nothing. Nor am I minimizing the problem or the importance of the proposal; I am simply trying to put its possible scopes and consequences into perspective.

Beware the dog

And the ever-haunting threat of believing that change happens within oneself and that the important thing is to do our own little bit.

Contrary to the old woman who fed the birds, in whose case the problem would have been solved when she stopped putting her own interest ahead of everyone else’s; nothing is as simple in what you propose.

+

What things are and their consequences

Things are not only what they are; they are also the consequences they bring with them. Often enough, measures hide unthought-of consequences behind a virtuous façade. Red meat consumption is an important ecological problem. In the last years many people in Europe have stopped eating meat as a consequence of an ethical decision related to the environment. This has exponentially raised the demand for other products, quinoa, for example. The unrestrained exploitation of quinoa (mainly grown in Bolivia and Peru) for European consumption has brought profound consequences to the land and the communities that produce it. Some of them good and some of them bad, but what looks like something from one perspective, looks like something very different from another.

A little obvious

What I am telling you is a bit obvious and you know it. I am just trying to restate the importance of considering the correlation of forces in every conflict when proposing an action. Because when we don’t, those who pay the costs will always be the others. “Stop travelling by plane”, at the end, is like saying that everyone should stay where they are and, as it happens, you stay next to the water well.

Forgive my honesty

To be honest, I find it a bit cheap that those who ate more meat, who lived from feast to feast, whom we saw licking their fingers for years, now come and tell us that we should all stop eating meat… equally.

As my friend Juan sums it up

At the end of the day, solving an ecological problem without considering social inequality is just another way to reinforce the colonial structure.

Pandemic

The current pandemic has already faced us with a situation where flights were momentarily restricted. At the same time, the world’s inequalities have been reinforced. The crisis has shown us in a brutal way that not all lives seem to be worth the same.

What we know today is that 16% of the world’s population has hoarded 60% of the vaccines, and it is the same with everything else.

To sum up

By trying to solve one problem, we may end up adding to another as collateral damage, deepening the asymmetry gap in resource distribution and cultural access. These problems are not equivalent, but while your influence in one field is symbolic, it is quite real in the other.

+

Closing time

Your blunt proposal has brought the issue to the table in a way that I find very positive. Perhaps I am wrong and my geographical and artistic position prevent me from noticing certain things. Perhaps my needs drive me to consider the situation in relative terms and I shouldn’t. Perhaps, sometimes, one should act before thinking. Perhaps I can’t see the whole picture. Perhaps there is a price to pay and someone has to pay it. Perhaps you are right and festivals should only invite artists who do not fly. Perhaps, inadvertedly, I am the old woman who feeds the birds… perhaps.

But perhaps not.

Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez

(Co director Lagartijas tiradas al sol)English Version: Juan Francisco Maldonado

RECOGNIZING SYSTEMIC RACISM IN DANCE

By Alicia Mullikin

As a first generation Mexican American woman of color in the dance world I have experienced microaggressions that have caused significant barriers to my progress as a dance artist and damaged my emotional health as a person of color—and yet, what I have endured is only a drop in the bucket. Through conversations and collaboration with other dancers of color and colleagues, we named some of our personal experiences in the dance world that reinforced systemic racism. Though this is not an exhaustive list, it sheds light on some problematic power structures that contribute to continued inequity in dance. Here are a few ways you may have participated in systemic racism in dance.

FOR EDUCATORS AND DIRECTORS:

FOR ORGANIZATIONS & GRANTORS:

As White and non-black POC in the dance community, complacency with systemic racism prevents us from seeing all the ways we benefit and participate in it. We recognize that looking at this list can feel debilitating as an artist, director, or educator. Fully realizing an equitable dance community will not happen overnight. You WILL make mistakes and you WILL fall short because these structures run deep and are ingrained in the very fibers of our country, communities, and studios, BUT it is work that we must do dutifully. Hopefully shedding light on these things will help us put one foot in front of the other on the necessary walk to a more equitable dance community. The next generation of dance artists deserve better than the racist structures we had to put up with.

Linked are a few resources we found helpful for dance artists committed to Anti-Racism.

Contribution Acknowledgement:

Albee Abigania (Lynnwood/Everett/North Seattle), DJ Baluyot (San Jose), Cheryl Delostrinos (Los Angeles/Seattle), Imana Gunawan (Seattle), Sue Ann Huang (Seattle), El Nyberg (Seattle), Noelle Price (Detroit/Seattle), Coral Taylor (Los Angeles)

Visual Artist:

Nalisha Rangel (Seattle)

INTERVIEW By Harry Burke

JIMMY ROBERT ON THE BODY, SPACE, AND POWER

“The words emerge from her body without her realizing it, as if she were being visited by the memory of a language long forsaken,” wrote Marguerite Duras in her 1990 short novel, Summer Rain. The notion of the body as a vehicle of language permeates the inquisitive practice of Jimmy Robert. Born in Guadeloupe, and based in Berlin, Robert — who works in performance, photography, installation, and film — uses the body to ask questions about how spaces are constructed, and what it means to see and be seen. His artworks are often formed through processes of translation and transition, as he constructs meaning out of the differences that exist between various sites, texts, and media. A rigorous attention to collaboration runs throughout his oeuvre, and extends even to his relationship with his artistic godmothers: Duras, Yvonne Rainer, and other feminist figures who have brought visibility to issues of desire and movement while problematizing how power operates within the visual sphere. Earlier this year, Robert staged a performance titled Joie noire at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, and is currently participating in the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial (until January 2020). To encounter Robert’s work is to understand that art can be judged as much for what it does as for what it is: viewership is a provocative and participatory process. Can you describe your work for the current Chicago Architecture Biennial?The title of the installation and performance, Descendances du nu, is a play on the French words for descending and legacy — its starting point is Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. I first performed the piece in a former synagogue in France. I was thinking about what it means to bring a body like mine into an art space with strong religious connotations while reflecting on Duchamp as a patriarchal figure — Sherrie Levine, Elaine Sturtevant, and Louise Lawler have all appropriated his work — and trying to locate myself between matriarchal and patriarchal figures. I wore a headpiece that looks like a staircase — I was like an architectural anomaly, or symbiosis. In Chicago, other performers are performing the piece on a staircase in a big cultural center from the late-19th century. It’s a neo-baroque extravaganza accompanied by a sound piece by Ain Bailey, and a text by Élisabeth Lebovici who writes about cabaret, Josephine Baker, camp, and the notion of the pedestal.

In 2017, you presented Imitation of Lives (2017) at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in Connecticut. The piece responds to the building’s iconic architecture. It evolved in dialogue with Lucy McKenzie’s painting Loos / De Bruycker marble, as well as David Hammons’ In the Hood, texts by Jayne Cortez, Marguerite Duras, Audre Lorde, and Lorenzo Thomas, and other references. Intertextuality is very important to you. Why?It’s a way of opening things up, of layering, and of showing that things are complex and can’t be reduced. Whether it’s language, literature, or painting, these are different forms of collaboration. Collaboration is vital within your work.It stems from a desire to learn from others: what their work is, what their work is about. I once worked with (artist and choreographer) Maria Hassabi and found a shared interest in the body becoming an object. Collaboration is expansive and nourishing. It’s a bit like appropriation, which is about absorbing different practices and concerns.Perhaps collaboration is consensual appropriation?Ha! There needs to be a deeper sense of responsibility about how things are appropriated and borrowed. In appropriation, there’s an archaeology of knowledge, of how you construct yourself and your practice. My relationship to Marguerite Duras has been obsessive: watching and reading everything, knowing I needed to process ideas about masculinity, femininity, colonialism, and desire. Appropriating is a way of devouring. It is a cannibalistic approach to art: devour it to emit it back, transform yourself, and grow.

You recently presented Joie noire at KW, Berlin, within the context of a program dedicated to the late artist and performer Ian White. What was your relationship to Ian?We met when he showed some of my films at LUX in London. Once, we saw a Michael Clark piece at the Barbican, and thought, “Ah, we could do that!” So we found a way to do something together by learning Trio A by Yvonne Rainer. It’s meant to be a democratic dance that anyone can learn. We weren’t dancers, and we thought, “Can we really do this?”, but we figured it out, and performed it at Tate Britain and MoMA. Ian’s particular interest was in how to change the dynamic of the auditorium, and how people interact with films. Through him, I became interested in challenging relationships to institutions, art, and its interpretation. What did Joie noire consist of?We traveled through different spaces in the building, questioning time, and how long the audience would watch and listen. Choreographing the action of looking — that’s what I’m interested in. In the work, there was a recording of Ian talking about embalming, which he gave me before he passed away. It’s a meditation on death, and the nightclub. We went dancing a lot, and thought about art at cruising bars: these places are not about reflection, but that’s how we used them. There were seemingly disparate elements, but historically connected, through AIDS and activism in the 1990s. It was important that the work be staged in Berlin, the last city of decadence.Why performance?I’ve always found representation to be failing. I’m interested in analyzing what questions come from this failure. I started with photography, which produces a distance. I wanted to challenge this distance. The body became a transition between the moving image and the still image. Performance feels political because the body, a site of interference and resistance, is there. You have to face it.

What Makes Performance the Required Medium of the Day?

Karen Archey on Ligia Lewis and Alex Baczynski-Jenkins

What is it about performance that makes it the required medium for any new art initiative today? Historically, performance has been unwieldy for institutions to exhibit and collect. It is incredibly resource-intensive, requiring time and space for rehearsal, audio-visual equipment hire and, most importantly, fair wages for performers. Staging a performance is notoriously expensive in comparison to, say, most painting shows, which don’t typically require continuous upkeep and financing once mounted. More challenging to stage, and thus less-frequently seen, the medium is one that museums and their publics have been slow to warm to.

This month marks the reopening of New York’s Museum of Modern Art after its absorption of the former American Folk Art Museum. The expanded MoMA is relaunching with The Studio, a space integrating time-based artworks within the permanent collection display. (However positive the project may be, the museum’s claim that ‘The Studio is the world’s first dedicated space for performance, process and time-based art to be centrally integrated within the galleries of a major international museum’ seems dubious, given the opening of Tate Modern’s Tanks in 2012.) Today, museums subsume entire buildings and real estate used for art springs out of the earth in Manhattan’s last underdeveloped parcel of land. Performance is a spark of life to these otherwise languid structures. It offers an immediacy and sheen of authenticity that counteracts the neo-liberal, tax break-funded initiatives in which the works are performed – pitting a sense of haptic touch against tempered glass and stainless steel.

Perhaps it’s precisely the soft science of working with and viewing other people that makes performance a refreshing counterpoint to an art industry that is increasingly commercialized and corporatized. Regardless of athleticism or ability, in dance traditionally made for the stage there’s a satisfaction – and, perhaps, seduction – in viewing the technique-driven, trained body of a performer. You could argue that the same holds true in contemporary performance. Artist Alicia Frankovich, for example, works almost exclusively with queer, crip or pregnant performers, and her improvised choreographic works come off as a celebration of community on stage.

Like Frankovich, there are countless artists, performers and choreographers whose practices are being developed as an embodiment of their politics, relation to others and communal engagement. Given that performance utilizes the material of others’ bodies, the primary substance of the medium is relation, and consciousness of such relationality is a defining hallmark. While issues surrounding responsibility and consent are not without their hiccups, arguably they are at least a forerunning concern for practitioners of the medium. As such, many of the artists working in performance today take social responsibility as their core material, combining the representation of a constituency in their work with the care in the material world necessary to help their communities flourish. This is evident in the work of Ligia Lewis, who investigates the limits of empathy in popular and relational representations of black people, and Alex Baczynski-Jenkins, whose choreographic work celebrates the public display of queer desire.

Born in the Dominican Republic, raised in Florida and living for most of her adult life in Europe, Lewis works as a choreographer, director, dancer and performer. After training in dance at Virginia Commonwealth University, Lewis began performing in other artists’ works before embarking on her own career as a choreographer. Living for many years in Berlin, a city known for its support of theatre, Lewis attended countless stage plays and performances, particularly at the Volksbühne. Spending so much time around the stage prompted Lewis to use the theatrical black box as material and site for her works. Her recently completed trilogy began with a reflection on race and representation within theatre. The first work, Sorrow Swag (2014), is a choreography for one white male, themed around the colour blue, and approaches issues of embodiment, gender and grief. The second, themed red and titled minor matter (2016), is a choreography for three dancers – often performed by two black men as well as Lewis herself. This energetic piece pulls from both vernacular dance, such as black American high-school step routines, and well-known works from the history of modern dance, including Maurice Béjart’s renowned 1960 piece Boléro. The work’s opening scene, in which a ballerina seductively stretches out her spot-lit arms in parallel above her head, takes on a different meaning when enacted by a black man.

Lewis’s latest work, Water Will (in Melody) (2018), concludes her trilogy and is themed in white. Choreographed for a cast of four women, Water Will takes as its subject willfulness and its uneven application to us depending on social markers such as gender, class and race. Inspired by feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s Willful Subjects (2014) and the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale ‘The Willful Child’ (1815), the work breaks with the expectation that, because its creator is a woman of colour, it must bear biting, direct social commentary. Water Will explores the concept of interiority through metaphors relating to femininity: the set is cavernous, dark, affective and wet – in the last scenes, the stage actually rains, as if crying. While Lewis is keenly attuned to the continued racialized persecution faced by people of colour, she has focused her practice on creating other possibilities for viewing and sensing the world in order to reflect on relation and empathy. Although Lewis is working on a range of visual arts commissions, she is also planning a new stage-based work for 2021.

Alex Baczynski-Jenkins is a choreographer who explores queer desire. Based in London and Warsaw, and of English-Polish heritage, Baczynski-Jenkins comes from a less traditional dance education than Lewis, with a focus on somatics (a field of movement studies that emphasizes the dancer’s internal experience). However, similarly to Lewis’s, his work is focused upon caring for a community, both representationally and materially. In a 2019 interview with Eliel Jones in Mousse Magazine, he states of his collaborators and performers: ‘Who you want to work with is who you want to share your life with.’

In 2015, as Poland’s right-wing government ascended to power, Baczynski-Jenkins co-founded, with Marta Ziółek, the queer and feminist space KEM in Warsaw. Located in a former factory, KEM initially functioned as a rehearsal and studio space to support other choreographers’ work. When the building was demolished to make way for new real estate, KEM took up residence in other institutions such as MoMA Warsaw (itself housed in temporary quarters) and Zachęta. Most recently, for KEM’s residency at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Baczynski-Jenkins and his collaborators Krzysztof Baginski, Ola Knychalska and Ania Miczko threw a series of parties called Dragana Bar that functioned as an underground safe space in a city where homophobic sentiments are increasingly common and condoned by a far-right government.

Like KEM, Baczynski-Jenkins’s own choreographic work is created through structures of communal care and interdependence. His most recent work, Untitled (Holding Horizon) (2018), was developed as part of the Frieze Artist Award and performed at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Inspired by KEM’s Dragana Bar, this durational work is staged in a dark room and based on the box step, performed tirelessly by a large group of queer dancers.

Other works choreograph everyday queer life. Us Swerve (2014) is an orchestrated choreography of men on rollerblades, encircling each other like pendulums, with desire as the gravitational force. The two-hour work was inspired by the artist’s residency at Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, where he watched men cruising on rollerblades at the waterfront. Baczynski-Jenkins’s choreography takes the normally private experience of yearning and celebrates its queering as a public act; his performers embody the jubilance, apprehension and vulnerability that comes with this transformation of private to public. One of the most enduring myths pervading our industry, from both within and without, is that art and its practitioners are disconnected from the material realities of labour. This toxic misconception serves to disconnect ethics from our practices, despite the art industry feeling the material consequences of real estate run amuck, the economic effects of forcibly flexibilized working structures and the socio-political effects of government-condoned racism and homophobia. That practitioners such as Lewis and Baczynski-Jenkins place representation and social responsibility so centrally in their art is an essential and invigorating rejoinder.

KAREN ARCHEY

Karen Archey is an independent curator and art critic based in Berlin.

Excerpt from a conversation between Tarren Johnson and Wojciech Kosma at The Performance

Agency Studio, Berlin, July 8, 2019

[…]

W: The only thing I thought about when driving here, was how wonderful it would be if the Settlers Lounge didn’t have any context. I could see it in a theater, a musical venue or in the street. So-mehow it felt like the content was preceding the context, because it didn’t rely too heavily on where it was happening.

T: The original structure of the Settlers Lounge was going to be a box of two way mirrors instead of the final steel framed structure. The atmosphere was shaped by the original design. Even though you could see through the partitions of the space, there was an indication of separation. For me it was really important to find the core and now I will build on it as the performance series continues and moves to different spaces. I really enjoy working in store fronts. I think there is an interesting engagement with the people that are walking by and watching us rehearse over a period of time. And a lot of people ended up coming by for the show with the speaker outside as an invitation.

T: What inspired me to make this piece was travelling to New Zealand, going to heritage parks and encountering stories about settler colonialism taught via physical postures of wax models. I was going in, literally looking at the physicality and asking myself what am I supposed to be getting from this still representation of a body and a posture in this context. Another element is about ma-nipulating individual and collective ideas of the past. I’m interested in emancipated authorship ap-plied to history.

W: So what happened to these representations during the piece?

T: Well, I perverted them horribly. I think Andrew Clarke menstruating from his mouth at the end of the piece wasn’t something you would see in a historical park.

W: I allowed myself to enter very emotionally into the work and experienced the music as sort of unbreakable, like a crystal…

T: Actually, I’ve been interested in the use of sound in psychological warfare. Music can set a tone for a situation and give you a lot of information about what you should be thinking or feeling.The composer I collaborate with, Forrest Moody, and I push a romantic piano music, evoking daytime television, past a certain limit. I’m not trying to alienate the audience, if people get alienated it’s be-cause they’ve indulged so much in their fantasies that they hit a wall.

[…]

BY Elizabeth Fullerton with/about Anne Imhof, 2019

Anne Imhof presents seductive, melancholy performance populated by beautiful, androgynous, sullen youths. Over six nights in March, the German artist staged Sex, her latest epic composition, in the Tanks at Tate Modern, cylinders that stored oil when the building was a power station and that were converted into performance galleries in 2012. Sex shared some similarities with Imhof’s powerful, angst-ridden Faust, which earned her the Golden Lion for best national pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Like that work, Sex featured dancers, musicians, and models in club gear singing, headbanging, and wrestling across different spaces over four hours. But Sex, shaped by Tate Modern’s three subterranean spaces and incorporating Imhof’s paintings and sculptures, was more elaborate and ambitious in scale than Faust. The South and East tanks were each dominated by a pierlike structure, one for audience members to stand on and the other accessible only to performers. The adjacent Transformer Galleries were lined with Imhof’s large-scale yellow and black paintings (“Gradients”), graffito works (“Scratches”), and silkscreen prints portraying her partner and collaborator Eliza Douglas with her mouth open in a silent scream. In this third area, which evoked the intimacy of the bedroom, performers sprawled on high plinths or crouched on shabby mattresses surrounded by smashed iPhones, beer cans, bongs, sex toys, and S/M gear. A mesmerized audience trailed the performers as Imhof coordinated her team’s movements by text message.

Sex is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago from May 30 to July 7 and travels to the Castello di Rivoli in Turin in 2020. I met with Imhof between rehearsals for a discussion of the production and her process.

ELIZABETH FULLERTON How did the Tanks’ industrial ambience and scale chime with your vision for Sex?

ANNE IMHOF I was interested in having multiple layers. The Tanks allowed me to make three overlapping pieces in one. I wanted them to bleed into each other, blurring all the time, so I was thinking how the different tempos could work together.

There’s a painting of a rotated sunset on the wall of the South tank, which was one of the initial images in the show. This vertical horizon line for me stands for an ending, for annihilation or death. In that Tank you’re looking into a landscape from an overlook platform, but actually you’re indoors.

By contrast, in the Transformer Galleriesthe kind of images I wanted to create resemble portraits. There is an element of cruelty when viewers can stare at an intimate moment unfolding that close up for as long as they want to. One of the choreographic sequences in this space involves frantically putting in order things that are lying around—a beer can, patent leather shoes, my bronze head sculpture. They are placed in a row with bongs and toothpicks. It was Eliza’s choice to use the Golden Lion as a prop. The lion ended up among the rest of the objects with a Stella Artois can on top of its wings. The idea was to make all the objects seem equal, and to use them as attributes to suggest a narrative about a person. The performance shifts from individual characters to a shared persona that is distributed over multiple people.

FULLERTON What is the relationship between your paintings and the performance in Sex?

IMHOF I chose these black and yellow works to be the predominant paintings in the show and this line that blurs in the middle has to do with a fluidity that I wanted the production to have. There’s something very violent in these two colors coming together. The way I work with painting and performance is very much the same. In the studio I execute some things myself and then hand over control to somebody else, as I do in my performances. I determined where the line and shadow go in the paintings, but they were made by a car painter. When I draw and paint there’s a moment of accident that I almost look for as a way of discovering what might come next. But it also gives me a feeling of panic because it’s not planned.

FULLERTON Were these paintings a response to the performance or vice versa?

IMHOF They were made at the same time and they influence each other. From the very beginning I worked closely with some performers, most significantly Eliza Douglas. Many of the movements and images were influenced by her art, as were the costumes and large parts of the music that we wrote in collaboration with Billy Bultheel.

FULLERTON Do the performers embody specific characters?

IMHOF Everybody brings their own personality and expertise with them, which you see in the improvisation. There are no particular roles assigned to performers but certain character attributes and gestures that are almost shared by everybody. People take them on at various points in the performance.

For example, there’s the character of the flaneur, who repeatedly enters the space simply for the sake of entering it, without performing a grand gesture that the others seem to be waiting for. Sometimes a gesture is introduced, then copied. You see a person turning with their hands held up, making a shadow on their face. Then another person copies them, so the gesture becomes an image that has a certain symmetry. I worked a lot with the motif of the doppelgänger.

FULLERTON You’ve said you regard your performances as sequences of images. Do these thread together a loose narrative or explore themes and moods?

IMHOF It’s nonlinear and quite loose. There are scenes, songs, sequences, and images that are fixed as well as unchoreographed “in-betweens.” These “in-betweens” are very important for the overall mood and aesthetics of the piece on a particular day. In general everyone brings in their own images and a lot is decided in the moment. It is a shared process of decision-making. Sometimes almost nothing is happening, which is an important aspect of the work for me. Sometimes it’s the opposite, and the piece suddenly peaks. It’s not just me who’s in control.

FULLERTON What draws you to that blankness, which also prevails in previous works such as Faust and Angst? It’s quite confrontational when the performers stare at you for minutes on end.

IMHOF I’m interested in the moment of uncanniness that comes from being looked at, when you discover something inside you that is maybe the thing you’re most in conflict with. Holding the gaze can also feel empowering

FULLERTON The zombielike performers enact the violence, pain, and discomfort of sex without the joy.

IMHOF There is a bit of zombie inside there for sure, when they dance the waltz as if they are undead, but I also think there’s a lot of mindless action around us, so why not take it as an image and put it in.

For me that moment may seem painful, but there is a joyful aspect in falling on the floor with somebody and then holding them, even if the embrace is almost violent. There’s something in it that’s very tender and real.

FULLERTON When you discuss the visual aesthetic with the team, do you instruct them not to smile?

IMHOF Yeah, we might jokingly say “don’t smile” if somebody new comes! This affect is also part of the exaggerated quality of the performance. In Sex I use lighting to create shadows behind people that are like a weird exaggeration of their own size. And then there is a moment where someone whips that massive shadow or where Eliza walks slowly toward the audience but the bouncing light makes it look like her shadow is going away. A huge shadow can look like an uncanny blackness from the neighboring tank.

FULLERTON How do you see the work evolving as it moves to Chicago and Turin?

IMHOF One of the piers is going to Chicago, where it will become something else—the only large-scale sculpture alongside paintings and drawings. I liked thinking of the objects and works having many lives, from hanging on the Tanks’ rough walls to being in a white cube space in Chicago. I’m interested in what art is and if it still has any vitality. With Sex I wanted to celebrate art as something undead.

STANTON TAYLOR on MICHELE RIZZO

Choreographer Michele Rizzo Reveals the Ecstasy and Unredeemed Power of the Nightclub

At Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, Rizzo’s performance ‘Higher.xtn’ unpicks the communal politics of the dance floor

4/4, a siren calls. We wait. Slow-steady, young ravers descend upon the lobby: from the left, then the right, then behind. Clad in second-hand sports brands, well-worn workwear and sundry leatherettes, they serve the leftovers of last night’s looks. Yet their movements are introverted, their gazes downcast. Once onstage, they shuffle about aimlessly as they sync up to Lorenzo Senni’s haunting synths. Casually self-absorbed, they seem oblivious to anyone but themselves. By the time the music shifts gears towards a slower beat, the dancers have settled into rows facing each other and move in perfect unison.

Higher.xtn comes as the latest instalment in an ongoing movement research project that choreographer and artist Michele Rizzo initiated in 2015. After studying at the School for New Dance Development and the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, Rizzo went on to produce the first version of Higher in collaboration with the Frascati Theatre and ICK Amsterdam. Originally developed for a classic black box theatre, the earliest version featured an extended light show and only three dancers – Rizzo himself alongside Juan Pablo Camara and Max Goran. Later on, the project came to encompass a series of large public workshops. These workshops in turn helped Rizzo refine the techniques he would use to drill the cadre of dancers at the Stedelijk into ecstatic unison. One exercise, for example, involved pairing the dancers off and having them improvise over extended periods while staring into their partner’s eyes. This was designed to help the dancers lose their bodily self-consciousness in the face of the other. Only then would another exercise start introducing the piece’s short yet precise phrases into these durational improvisations, step by step. And though some dancers understandably described the marathon rehearsals as rewarding but exhausting, the characteristically authorial Rizzo was more reserved: ‘…you know, it was only two weeks.’

Performed twice a week over the course of a month as part of the exhibition Freedom of Movement, Higher.xtn quickly grew into considerable social media success. It now seems that Rizzo is well poised to join the growing number of choreographers working as frequently in museums as they do in theatres and festivals. But compared to the languidly immersive performance environments of Maria Hassabi, Anne Imhof or Adam Linder, Highert.xtn stands out for its assertive theatricality: an unambiguous stage, a clearly defined beginning and end, relentless synchronisation, and a rejection of all things ‘participatory.’ On the phone, however, Rizzo conceded that this sense of theatricality was partly an unintended consequence of the piece’s runaway success. During the first performances, visitors were somewhat confused when they initially encountered the dancers awkwardly shuffling to themselves in the stairwells and halls; some even wanted to join. This ambiguity, Rizzo suggests, would probably have been more in line with the way people perceive things with their bodies as they wander through an exhibition space. By the last performance, even visitors who’d come half an hour early found themselves jostling for a place to stand, let alone sit, in the Stedelijk’s crowded lobby, and you could feel the anticipation swell with every minute the stage was empty. The audience had arrived and they wanted a show.

But beyond these translations between museum and theatre, there is something more sacred at work: the translation between the experience of clubbing and its representation. The image offered is, paradoxically, one of private transcendence in the midst of complete social determination. In the pursuit of ecstasy, the dancers submit wholeheartedly to each other and more importantly, to the rhythm that holds them in step.

In an early statement on the piece, Rizzo speaks of trusting in dance as ‘the practice that compensate[s] for the fact that we can never be each other,’ and thus ‘we attempt in becoming one.’ What Rizzo shows us is an inverted technology of the self: one where discipline does not serve to cultivate the individual, but rather dissolves it altogether. He shows us the individual body ventriloquised in the service of something greater than itself. But the question remains: in service of what? Here, the vision of transcendence doubles as a vision of community. Much like protests, night clubs and festivals are one of the few forms of IRL assembly still tolerated as a pressure valve to daily life under capital. Unlike protests, though, these assemblies are meticulously guarded spaces, blissfully free of social conflict and subsequently dialogue: bouncers over barricades, community over class. At its most powerful, Rizzo’s Higher.xtn not only shows us the ecstasy of social communion, but also its glaringly unredeemed potential. Being together is beautiful, just as long as it’s not with everyone.

Michele Rizzo’s Higher.xtn was performed in January and February at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, as part of the exhibition ‘Freedom of Movement’, which runs until 17 March 2019. His new piece Deposition premiered at Kunstencentrum Buda, Kortrijk, Belgium, on 20 February. On 1 March, Rizzo will hold a workshop at the Stedelijk Museum.

Kate Brown on Nora Turato

‘Hysteria Is Still Taboo’: Performance Art Dynamo Nora Turato on Why the Art World Still Isn’t Ready to Hear a Woman Scream

The Croatia-born, Amsterdam-based artist is on a hot streak.

She performs in the typically quiet, hallowed halls of museums, galleries, and even churches. She storms around; she gets hysterical.

Now, she’s working on two solo shows that open in early 2019, one at arts center Beursschouwburg in Brussels and the other at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein. Last week, she wrapped up her two-year stay at the prestigious Rijksakademie residency in the Dutch capital.

This rapid-fire pace is fitting for an artist whose work is as dynamic as Turato’s. Typically setting herself up against a backdrop of dizzying text-based posters or typographic videos, Turato presents brazen, wandering monologues using her most transgressive artistic tool: her voice.

“Rarely do you see artworks where the female voice is going to these extremes,” Turato tells artnet News from her home in Amsterdam. “It’s usually trying to be sexy, calm—like a voice operator. And rarely do you see the female voice being used hysterically.” (“Sorry… I just ramble,” says Turato to an audience after spewing a bunch of sounds in her recent performance leaning is the new sitting at Vleeshal Markt in Holland. “I often say ‘sorry’ when I mean ‘thank you,’” she continues. “But I was only given a nail file and ‘sorry’ to cut my way out.”)

Turato enters into typically male-dominated spaces in an armor of conspicuous, colorful garb—like a tailored Balenciaga suit paired with spiked heels. And she starts talking. She goes on for half an hour (right around the length of a punk record) and, with her clipped melodies, she races through a stream-of-consciousness tangle of references that range from advertisements to book excerpts, movie quotes, and social-media posts. As artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein described it, “the effect is a bit like listening to ‘The Wasteland’ as composed by a bot and broadcast via Alexa.”

Origin Story

Croatia’s bloody war of independence broke out in 1991, the same year the 27-year-old artist was born. Luckily, she says, her family was not directly involved, so her trauma is much milder than that of many others from her generation. But, nevertheless, she came of age in the context of Croatia’s hardened postwar and post-socialist music scene emboldened. After high school, she moved to Amsterdam to study graphic design at one of the city’s top art schools, the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, and took up work as a full-time graphic designer.

Turato says she was always performing on the side. “I never became an artist on purpose,” Turato says. “I’m doing this by accident because the art world was the first world that let me do this.”

It’s true that her work could just as easily be adapted to cinema, avant-garde theater, or fold back into music. But after a long spell as a musician in Croatia, she found the punk scene boys’ club boring; the Dutch art world proved to be more engaging and accepting. “There’s still a genuine surprise when women do something good in music,” she says.

And like many immigrants, she now feels at home both everywhere and nowhere. “I had to change my ways a lot to exist in Holland,” she recalls. “There is something about living in the West and having a distance from it. But I also have distance from back home. I am always somewhere in between.”

The spoken word artist explores the feeling of not-quite-belonging in her performances. At Kunstverein Bielefeld in Germany earlier this fall, Turato pounded around the institution in a cobalt blue suit jacket and a vibrant orange turtle neck that matched her dyed hair, frantically listing off the things her peers have obsolesced while she glared back fiercely into a crowd that quietly lined the walls.

“My generation… My generation is killing hotels, department stores, chain restaurants, the car industry, diamond industry, napkin industry, home ownership, marriage, doorbells…serendipity…” She speeds up; her list goes on. With raucous acceleration, you can almost feel the BPMs turning up—changing a tangent into a punk anthem that’s too frank to be cynical.

Finding a Home in the Art World

Turato’s experience in advertising is evident in her magnetic, bold, sans serif posters, which bear snappy slogans reminiscent of advertising billboards. She prefers the simplicity of print because it recalls inexpensive merch seen at music venues. She doesn’t want to make art that’s too precious.

But while her ephemera aims to look both casual and replicable, her presence is anything but that. “I wondered what could come next after this whole ‘don’t-give-a-fuck’ moment,” she says, reflecting on the abject trend in contemporary art that surrounded her. That’s partly why she decided it was important for her to dress well.

Her formalism in dress stands in stark contrast to other performance artists of the moment, who opt rather for more unstudied or so-called effortlessness fashion. (Anne Imhof’s Golden Lion-winning performance at the Venice Biennale in 2017, for example, included performers that were meticulously dressed to look like they had just rolled out of bed.) “I do give a fuck, so what do I wear if I really do give a fuck?” asks Turato.

As she steps into character, Turato describes going into “complete autopilot.” (She memorizes her lengthy scripts beforehand.) “If I was doing what I do in Croatia, I would be seen as nothing short of insane,” she points out. “I don’t think Croatia would be ready to have a woman talk like this yet.”

Depending on the mood and composition of the audience—the more men present, the more skeptically she says she is received—Turato reworks her lines each time, ramping up particular snippets. “It’s like a band performing their favorite song,” she says. Lines are repeated like a hit chorus, but a little differently every time.

Her work can still be a tough pill for audiences to swallow. At Manifesta 12 this summer, Turato was taken aback by the audience’s reaction to her performance at a baroque chapel in Palermo during the opening days of the nomadic European biennial. Some people left vicious comments in the book at the front of the church, writing that she was a “crow in paradise” and a witch. “It reminded me of south Croatia, where it is really conservative and Catholic and uptight,” she says.

Turato is showing us that, even today and even in the more progressive corners of the world, many are not quite ready to have a woman shriek, rant, gossip, and whine at them, or stare them down. She wryly notes how many words there are to negatively describe a woman’s voice when it does not fall into the soft-spoken category. “I feel like men are still not capable of listening to a woman for 25 minutes straight without saying anything,” she says. “Hysteria is still taboo—no one wants to be seen as hysterical. You do so much by just doing that.”

MATTHEW MCLEAN on Trajal Harrell

Made to Measure

Trajal Harrell talks ‘realness’, daydreaming, and his performance Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (S)

Trajal Harrell is in London to perform Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (S) (2010) at Sadler’s Wells – the UK debut of this piece, which forms part of Block Universe, the performance festival whose impressive second edition also featured UK premieres of works by Martin Spangenberg and niv Acosta, and new commissions from Jesse Darling and Raju Rage, Grace Schwindt and Erica Scourti, among others.

From 2009 on, in venues from Vienna to Rio de Janeiro, Harrell has mapped the possibilities of this thought across a series of performances, each a kind of remix of the other, nominally distinguished by sizes, like garments: from (XS) to (XL) to (M2M) – ‘made to measure’. Along the way, he’s been nominated for a Bessie (The New York Dance and Performance Awards), lavishly praised by the New Yorker and the New York Times, and (bizarrely) hailed as ‘the next Martha Graham’ in the Huffington Post.

The idea of producing the work in sizes was inspired, Harrell says, by the different sizes of the snowballs sold by David Hammons in his Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), as well as Rem Koolhaas’ 1995 volume of the OMA archive, S,M,L,XL. (Harrell is passionate about Twenty Looks … ultimately taking the form of a publication).

Yet the sizing of the work is also a winning – and winningly transparent – negotiation of the choreographer’s position as a practitioner without a fixed audience or network of patronage. ‘I never had the dream of building a company that will perpetuate itself after I die’, he says, the company model having, he feels, ‘fallen apart’ for choreographers of his generation. As such, variability is key: a visual arts institution (Harrell has himself just completed a two-year residency at MoMA) with a regular flow of busy visitors and limited dedicated performance space might welcome a short commission in a way that a dance theatre selling tickets might not. ‘Who wants to hire a babysitter and come out for a ten-minute piece?’ Harrell asked in a post-show conversation at Sadler’s Wells. (As it happens, (M) and (L), each usually clocking in at around two hours, tour the most.)

Harrell explains that the multiple versions of Twenty Looks … also ‘work against the idea of having a specific viewer or an ideal audience’, which is to say its explicitly modular format puts upfront the impossibility of there being any priority within the series. It’s possible to see the whole series – each work was performed in sequence at The Kitchen in New York in 2014, for example – but no size is definitive, much less any one night’s performance of it: no experience of any part of the work is the ‘real thing’, and every experience is.

‘Realness’, as it pertains to original Ballroom culture is, indeed, one of the piece’s key occupations. To quote Dorian Corey from the famous 1990 Jennie Livingston documentary from which Twenty Looks … subtitle derives, ‘realness’ in this context means ‘undetectable’: a mode of self-presentation that allows the performer to ‘walk out of that ballroom into the sunlight and onto the subway and get home, and still have all their clothes and no blood running off their bodies’. ‘Realness’ is practical and tactical – a matter of appearance and perception (and survival). More fundamentally, is not a question of being ontologically identical to something or of inner essence: ‘realness’ is conditional on not being identical to something.

‘Realness’, as it pertains to original Ballroom culture is, indeed, one of the piece’s key occupations. To quote Dorian Corey from the famous 1990 Jennie Livingston documentary, Paris is Burning, from which Twenty Looks … subtitle derives, ‘realness’ in this context means ‘undetectable’: a mode of self-presentation that allows the performer to ‘walk out of that ballroom into the sunlight and onto the subway and get home, and still have all their clothes and no blood running off their bodies’. ‘Realness’ is practical and tactical – a matter of appearance and perception (and survival). More fundamentally, is not a question of being ontologically identical to something or of inner essence: ‘realness’ is conditional on not being identical to something.

In this way, there is a temptation to read the piece in terms of erasure, re-insertion and the righting of historical injustices. There is scope for redress: postmodern dance is overwhelmingly white; sexuality in much of the Judson group’s works is oddly illegible, given that many of its key figure are or were queer; and Vogueing, while hardly unacknowledged (I can’t get over the vine of two white tweens death-dropping in a school gym), lacks institutional recognition. Yet, as Harrell told Ariel Scott in a 2011 interview: ‘I don’t start from a politics to make my work.’ While he’s happy, even proud, if Twenty Looks … increases the visibility of Vogue and Ball culture, it’s not his primary aim: ‘I am not a Voguer,’ he tells me ‘and I have never felt that Vogueing needs me.’ (Again, not being a dyed-in-the-wool exponent of the thing he’s performing seems key to kind of realness that interests Harrell.) Twenty Looks … was instead a way to break out of some of conceptual dance’s more deadening tendencies. ‘For a time, there was not a lot of movement,’ he puts it diplomatically. Harrell’s performance at Sadler’s Wells, in contrast, though it has its static moments, is essentially all movement – slouchy at times, pointed at others, febrile in its intensity, each gesture seeming almost to vibrate. For all its elegance, it’s also tense – I was struck by a walk in which Harrell’s arms are subtly held out just above his hip, as if holding an invisible hoop. Growing up in south Georgia, Harrell told Scott in the 2011 interview, meant: ‘I really fought […] even to cross my legs.”

‘I always say: “I don’t know how to make a dance,”’ Harrell admits when I ask him about his working method. His research usually begins a year before entering a studio with other dancers – reading, listening to music, practicing on his own body – but he is reluctant to rely on predetermined formulae. Though his choreography is becoming increasingly refined in its movements, treating the body as object (perhaps, he speculates, one result of spending time in visual arts institutions), there’s still a sense of being without a ‘recipe book’, in Harrell’s words.

Yet in the history of dance – on the stage and in popular crazes, in Hoochie Coochie shows and all that which he calls ‘dance before it knew itself as “dance”’ – Harrell does have a recipe book, or a scrap book, at least: a dossier of gesture and inspiration. Recently, while researching the development of the Japanese dance theatre Butoh for pieces such as The Ghost of Montpellier Meets the Samurai (2015) – another ‘cultural fiction’ hinging on fusion, this time an imagined encounter between Tatsumi Hijikata and Dominique Bagouet, the star of France’s nouvelle dance who died of AIDs at just 41 in the 1990s, in a New York bar – Harrell discovered that Hijikata had been influenced by Catherine Dunham, the influential African-American choreographer, whose repertoire drew on her anthropological fieldwork in Haiti. Tracing a line from Butoh to Voodoo: it starts to make sense, in the light of such semi-historical conjectures, that Harrell should sometimes refer to dancing as a kind of ‘archiving’.

Just as in Twenty Looks … runway fertilized postmodernism, historical content seems to spark Harrell’s inventiveness – his ‘addiction to the past’ (in another paradoxical manoeuvre) ‘frees my imagination’. ‘I don’t know if I’ll ever get fully into abstraction without history,’ he says. This commitment to the past is striking, given that dance compared to, say, painting, has a history backed-up by an extremely partial record, Harrell embraces the gaps. (Though its widely accepted as the pivotal moment in 20th-century dance, no-one can confidently say what Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1913 Rite of Spring actually looked like). ‘If you’re a choreographer, you have to love that problematizing,’ he says; if he can see too much of a moment, too concretely, ‘it becomes too didactic, too mimetic’. I wonder whether, as performance increasingly becomes the subject of institutional collecting, this will change. ‘That’s a big issue – how’s that done, what the parameters are,’ Harrell says, though he’s receptive to the idea; thanks to the likes of Tino Sehgal, Harrell thinks the market for dance works will be utterly different in 20 years’ time, though he doesn’t know how. For now, then, more research, more speculation, more realness, more imagination. To close, I ask Harrell if he was a daydreamer as a child. ‘I was! I am a daydreamer as an adult too. I have to think more and more about what do I want to with my time, and I think I really need more time to daydream.’

Open letter: #metoo and Troubleyn/Jan Fabre

By (former) employees and apprentices at Troubleyn

september 2018

In the interest of the audience and the wish to inform future generations of performing artists, we, former employees and interns who have worked with Jan Fabre in the context of Troubleyn vzw, have come together to share our experiences and to raise our voices in the context of #metoo and its associated social shifts.

This collective response is prompted by statements made by Jan Fabre during an interview with the public broadcast station VRT on Wednesday the 27th of June 2018. In the interview, Fabre shares his thoughts concerning the results of a survey on sexual harassment commissioned by the Flemish Minister of Culture, Sven Gatz.

The starting point for the interview is the headline “1 out of 4 women in the cultural sector experienced sexual harassment in the past year”. On camera for the interview, Fabre responds with surprise and disbelief when these numbers are presented. He says that he is supportive of the actions and measures taken by the Ministry of Culture, but adds that “there is also something dangerous about this. Because, the relationship, the secret bond between director/choreographer and actor/dancer…. you will in fact also destroy and harm it incredibly”.